PAN UK’s recent “Food for Thought” report definitely provides some nourishment for the mind to reassess the safety of our food in the Asian region.

Despite having one of the world’s most comprehensive food monitoring and regulation systems in EU, the report highlighted that the various food produce being supplied to the school children in UK should be revaluated for safety and quality.

This is because the produce supplied have been tainted with pesticide residues, putting the school children potentially at an even higher risk to health complications.

An analysis of the UK government pesticide residue testing data from 2005 to 2016 showed that overall 123 different pesticide residues were found in the produce supplied to school children.

Pesticide residue is ‘the detectable trace of any pesticide that remains on or in food. Due to the systemic nature of many pesticides, residues are contained within the produce itself and therefore washing the surface won’t remove them.’

PAN UK’s report also indicates that these school children are being exposed to pesticides at higher levels through the produce supplied as compared to the produce in the supermarket.

Children in Asia Pacific fare far worse largely due to the lack of adequate and more stringent regulations on the use of pesticide and food safety. This draws back our attention to the various poisoning cases that have taken place and continue to do so in our region which still lags behind in food monitoring and regulation in general.

Chlorpyrifos, an organophosphate was commonly found as a residue in most of the produce tested based on the report. Organophosphates like chlorpyrifos are toxic to children and have been linked to cancer, learning problems and various developmental disorders.

In 2015 in Po Ampil, Cambodia the brain harming pesticide chlorpyrifos have been found to be used nearby schools. Similarly, a Nordic study (Skretteberg et al 2015) revealed the presence of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from the Southeast Asian countries with residues most frequently found in guava, pitaya, chili pepper, chives and basil.

Multiple incidents of pesticide poisonings due to ingestion of pesticide-laced foods (fruits or vegetables) have been reported in Asia and continue to take place almost every year.

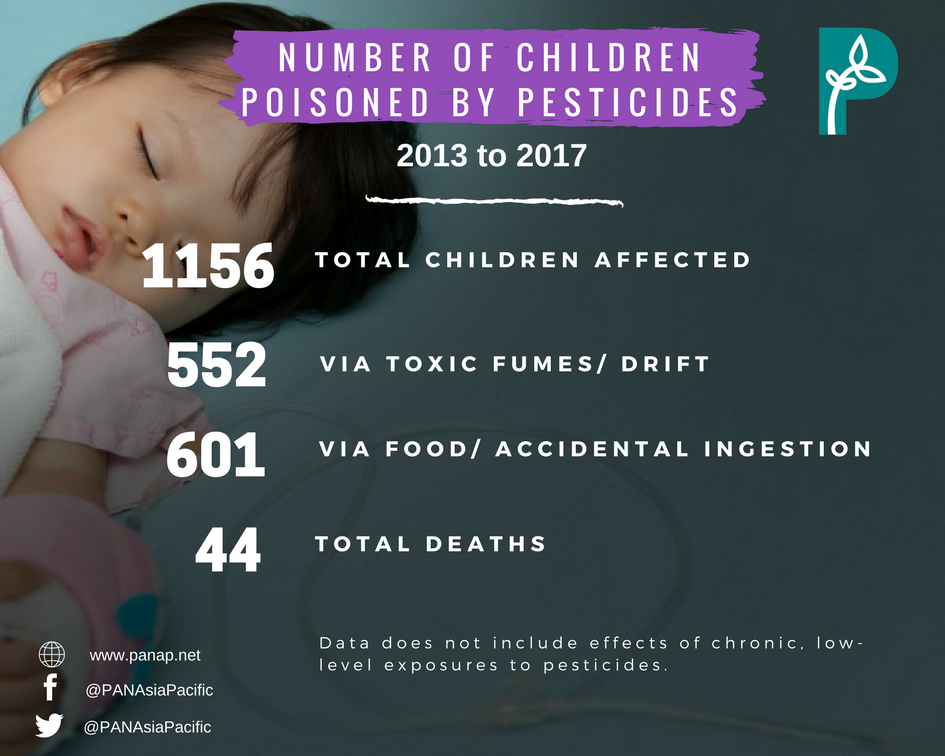

Drawing on PANAP’s POC Watch from the period 2013 – 2017, more than 1156 children around the world have been poisoned. However, the extent of poisoning is still not fully dealt with as many cases still remain undocumented in Asia.

Monocrotophos also an organophosphate insecticide was responsible for the deaths of 27 children in Bihar, India in 2013. The acutely toxic insecticide found its way to the children’s mid-day meal leading to the tragic situation.

In Cambodia, at least 50 children and half a dozen adults fell ill after eating pesticide-laden food in 2013; and 700 people (of which 400 are children) in 2015. In Malaysia, at least 30 people and one child were poisoned by carbamate that led to one death in 2016.

Although this type of pesticide has been banned in many European countries, there are no strict restrictions or regulations on the use of monocrotophos throughout Asia.

PAN UK’s Food for Thought reported the presence of multiple pesticide residues among the produce saying “Even within this limited research study, some samples have tested positive for residues of up to 13 different pesticides.”

An apple has been found not only tainted with chlorpyrifos but also with other 11 pesticide residues including carbendazim, fenoxycarb,and imazalil.

“Despite the likelihood that these multiple substances do interact with each other on some way, there has been little research into the combinatory or ‘cocktail’ effects of exposure to pesticides.

“One recent piece of research from France has shown clearly that combinations of pesticides found in food are more toxic when combined than when present in isolation. The results showed that a combination of five pesticides found in food caused damage to DNA.The ‘cocktail effect’ has in fact long-been recognised as an area of concern in the UK,” the report added.

The impacts of multiple pesticide exposure on a child in the long run is still uncertain and is a serious concern because the scientific community has little understanding over the complex nature of the different chemical interactions.

One hundred percent of raisins analysed had multiple pesticide residues, with soft citrus, pears and strawberries all close behind. This is definitely worrying!

This situation calls for better monitoring in Asia especially when there are many loopholes present in the current way of examining our food safety.

The authors of the report have called for the government to supply produce for school children from local organic farmers (or those consciously minimising their pesticide use) to not only protect children’s health better but also to boost the British organic sector. Accordingly, it would only cost $1 pound extra per child per day to make that important change.

PAN UK urged the Department of Health to raise the standards on pesticide regulations as UK prepares to leave the EU to ensure better protection of human health. This would ensure a thriving and truly sustainable agriculture sector.

The report’s launch is laudable and timely as the momentum for agroecology is growing. The call on the need for the world to transition from chemical intensive agriculture to one based on agroecology has been made even stronger with the report by UN Special Rapporteurs Hilal Elver and Baskut Tuncak earlier this year.

Agroecology-based agriculture works in harmony with nature and is free from pesticides. Documentation of agroecology farming approaches shows that it is a better option for consumers, and provides better livelihoods for rural workers and farming communities. Although laborious and may take time, conversion to agroecology brings about tremendous benefits in the long run.

Take Action >>Protect Children in rural communities against pesticides

Discussion about this post