PENANG, Malaysia – China’s rise as an economic and political power – and along with it its increasing appetite for land and resources – is one of the single biggest threats to the rights and livelihood of farming, fishing, and indigenous communities in the region today.

Thus concluded the two-day strategy meeting organized by PAN Asia Pacific (PANAP) for its “No Land, No Life!” campaign. Ten organizations from seven countries, including officials of the regional peasant group Asian Peasant Coalition (APC) joined the meeting held in Penang, Malaysia on January 27 and 28.

China’s rise

PANAP noted that Chinese loans, aids, and investments, many of which are now packaged as part of the so-called Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), are funding a wide array of projects (nearly 1,700 projects since it was launched in 2013) to improve the economic giant’s trade connectivity with the rest of Asia, Africa, and Europe. This “21st-century Silk Road,” however, is also paving the way to the further physical, economic and cultural displacement of already impoverished rural communities along its path.

In Pakistan, China is expected to shell out a total of US$67 billion mostly in investments for development projects spanning from Gwadar in Pakistan’s Baluchistan province to Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang province under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Tagged as BRI’s flagship project and launched in 2015 during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Islamabad, the CPEC plans to complete infrastructure, energy, and communication projects in 15 years to connect nine special economic zones (SEZs) and other Chinese investments along the corridor.

Among the projects is the further development of the Gwadar Port by China Overseas Port Holding Co. (COPHC). The company was awarded the contract for the construction and management of container berths, terminals for bulk cargo, grain, oil, floating liquefied natural gas, and Ro-Ro (roll-on, roll-off), expressways, international airport, desalination plant, and coal-fired power plant, as well as a 2,292-acre (927 hectares) SEZ adjacent to the port.

The Gwadar Port, strategically located in the Arabian Sea, offers the Chinese the shortest path to the oil resources in the Middle East and Africa, and to the markets in Europe.

Similarly, Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port provides China with strategic maritime trade routes. The port located south of the capital Colombo was built on loans from the Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM) which the current administration had been struggling to pay back. In exchange for the unpaid loan , the Sri Lanka Ports Authority agreed to give away 70% of the port on top of leasing around 15,000 acres (6,070 hectares) of adjacent land for 99 years to China Merchants Port Holdings Co., Ltd. (CMPort) for development as industrial zone. The Chinese state-owned company has already begun further development of the Hambantota port including the construction of an airport, numerous highways, factories, oil refineries, and the industrial zone.

Meanwhile, in the capital, the Colombo International Finance City – or more popularly known as the Colombo Port City – is being funded by the China Communications Construction Co., Ltd. (CCCC) and developed by the China Harbor Engineering Co., Ltd. (CHEC). The said project is so far the largest single foreign investment, and the largest infrastructure undertaking ever in Sri Lanka. Expected to be completed in 2041, the project will build a race track, yacht marina, mini golf course, exhibition center, luxury hotels, high-end shopping malls, apartments, and restaurants on 269 hectares of reclaimed land.

Chinese firms also have a number of infrastructure projects lined up in Cambodia. In January this year alone, the Cambodian and Chinese governments signed multiple agreements on projects amounting to billions of dollars in concessional loans during the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Summit (initiated by China in 2015 to facilitate cooperation among Mekong countries in the development of the sub-region) in Phnom Penh. Among them is the US$2-billion 190-kilometer highway that would connect the tourist-popular province of Sihanoukville to the capital Phnom Penh, and potentially “one of the world’s biggest airports” in Kandal province.

Aside from being Cambodia’s main trading partner and biggest investor, China is also among the top holders of economic land concessions (ELCs) in the country. Through ELCs, local and foreign individuals and companies are able to control vast tracts of land in any part of Cambodia. Of the 136 ELCs awarded to foreigners since 2001, Chinese companies hold 42 ELCs over 356,560 hectares of land.

Massive displacements

China’s so-called “development” projects in these countries, however, have resulted and are threatening to result, in the expulsion of people from their homes and sources of livelihood. In Pakistan, for instance, the further development of the Gwadar Port means the potential dislocation of thousands of traditional fishing communities living in the coastal areas of one of the country’s poorest and most volatile provinces.

The Hambantota Port project in Sri Lanka, on the other hand, is feared to displace farming communities which have long been productively occupying the land covered by the project, while the Colombo Port City project has already begun to negatively affect fishers, small tourism-related business operators, and others relying on the sea for livelihood. In Cambodia, hydropower projects and ELCs overlap with the local people’s farmlands, forests, and rivers, resulting in the forced and often violent dislocation of thousands of small-scale farmers, fishers, and indigenous peoples.

Challenging traditional powers

In Indonesia and the Philippines, the Chinese have also signed several investment and loan deals for the construction of roads, railways, ports, and airports, as well as for the development of agro-industrial (mainly plantations), tourism, and mining projects. The deals, however, do not mean these countries are substantially shifting alliances from the traditional political and economic powers, the United States (US) and Japan, to China, PANAP noted. But it is clear that China is sending signals that it aims to challenge these powers even in their own turf.

The Duterte administration’s infrastructure projects under its “Build, Build, Build” program threatens to displace thousands. The MRT-7 project will clear 300 hectares of agricultural land and displace 1,000 farming families in Bulacan (from the presentation of KMP)India – China’s historical rival – remains a strong ally of the US and Japan, as well. The US and Japan, along with international financial institutions such as the World Bank (WB) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), continue to be the main source of funding for the country’s “development” projects. Currently, among the main threats to peoples’ access to and control over land are the development of national investment and manufacturing zones (NIMZ), the Public Private Partnership (PPP) for Regional integrated Development Enterprises (PRIDE), SEZs, and the 2,700-square kilometer Coastal Corridors being funded by the ADB.

Increasing repression

But the region’s rural population refuse to passively accept the loss of their land and livelihood and have been strongly fighting for their collective rights. This is despite the violence, usually by the state, being committed against rural communities and their supporters resisting land and resource grabbing.

Based on the PANAP partners’ sharing, there are ongoing and systematic efforts to silence people’s organizations and non-government groups, the media, and even political parties that are critical of the government’s role in large-scale land acquisitions.

Everywhere, governments and land grabbers have been harassing, filing trumped up charges, arresting and detaining, and killing, among others, individuals and organizations that opposed land-related development plans and investments that threaten to negatively affect the people. From July 2016 to December 2017 alone, PANAP has monitored 110 reported killings of farmers and land rights activists.

Defending the right to land and life

During the meeting, PANAP partners from the Coalition of Cambodia Farmer Community (CCFC); Aliansi Gerakan Reforma Agraria (AGRA) of Indonesia; Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP) of the Philippines; Andhra Pradesh Vyvasaya Vruthidarula Union (APVVU) and Tamil Nadu Women’s Forum (TNWF) of India; National Fisheries Solidarity Movement (NAFSO) of Sri Lanka; and Roots for Equity and Pakistan Kisan Mazdoor Tahreek (PKMT) of Pakistan, shared the strategies the people employ in asserting their right to land.

In Sri Lanka, for instance, NAFSO is among the conveners of the People’s Movement against the Port City (PMPC) which is composed of communities, the civil society, members of the academe, and the religious, and has been conducting information and education campaign on the impact of the Colombo Port City project, as well as organizing fora, petitions, protest actions, and other activities against it.

In Pakistan, Roots for Equity and PKMT have initiated national campaigns against land grabbing, which activities include exhibits in communities and schools and publications.

In India, communities have been filing petitions for the government to revoke the development permits of unutilized SEZs (which according to APVVU is 60% of the 424 SEZs) and to give them back to the communities.

In Cambodia, CCFC has been conducting fora and training to educate farmers on their land rights and on how to contest ELCs.

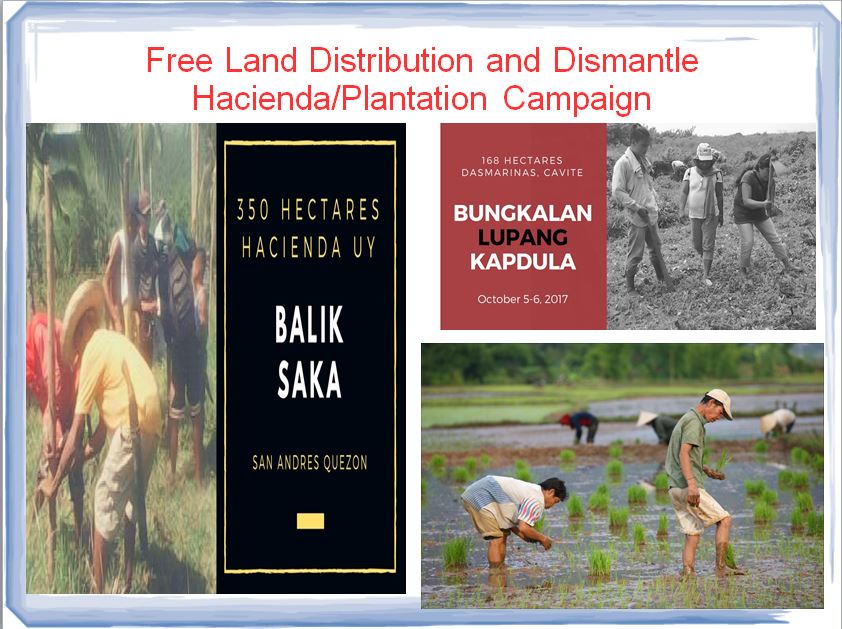

In Indonesia and the Philippines, affected peoples and communities organized themselves with the help of AGRA and KMP respectively, and have been conducting land occupation and cultivation campaigns to assert their control over contested land.

Through the “No Land, No Life” campaign, PANAP and its partners hope to build on these national and local strategies and victories to further advance the advocacy against land grabbers and human rights violators at the regional level.#

(Learn more about the “No Land, No Life!” campaign here)

Discussion about this post