This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that was adopted by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly on Dec 10, 1948. Considered a milestone document that proclaimed the inalienable rights that everyone is inherently entitled to as a human being, the Declaration has set standards to meet equality, justice, and human dignity.

The reality, however, is that even the basic human rights of the people continue to face serious challenges and setbacks, especially for the most vulnerable and poorest sectors such as those in the rural areas.

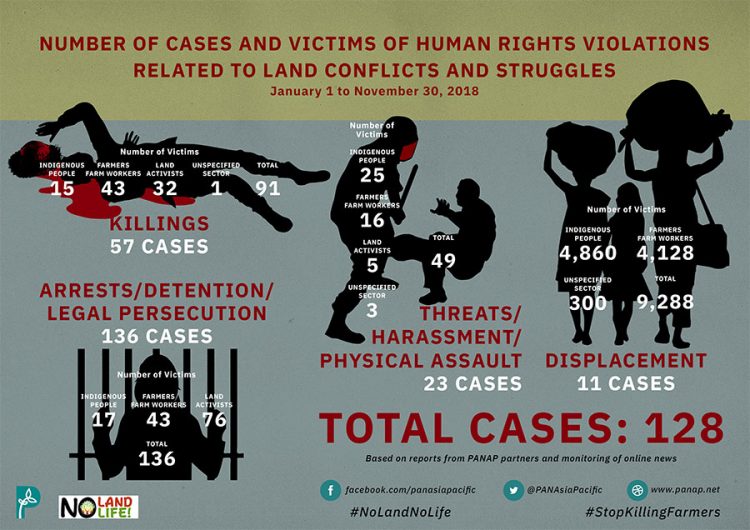

Our Land & Rights Watch 2018 yearend report paints a grim picture of the state of human rights of farmers, farm workers, indigenous people and advocates of the people’s right to land and resources. Every week this year, two are being killed for resisting land grabs; three more are being arrested and detained. Overall, we have monitored 128 cases of killings; arrests, detention, and legal persecution; threats, harassment and physical assault; and displacement that are related to land conflicts and struggles in 21 countries. (Download the full report)

The rise of authoritarian populism – from the Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte to Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro – has a profound impact on the rural communities that are asserting their legitimate claim to land and resources as a matter of people’s rights and social justice. Faced with intensifying threats of physical, economic, and cultural displacement due to government and/or corporate takeover of their lands for mining operations, plantations, tourism, infrastructure development, etc., communities of farmers and indigenous peoples around the world are compelled to defend their rights. Displaying little tolerance to opposition, such resistance is conveniently branded by authoritarian regimes as an “insurgency” of a small group of people; is inconsistent with the will of a supposedly overwhelming majority (which the populist regimes claim to represent); and purportedly contrary to national development. This creates an environment of impunity in the rural areas for local and foreign corporations, landlords and warlords (including local politicians), state forces, and paramilitaries and private armies at the great expense of the human rights of affected communities.

Based on data from the Land Matrix, there are about 1,591 concluded land deals involving foreign corporations or countries leasing or purchasing lands in low-income and middle-income countries worldwide covering almost 49.2 million hectares. Almost a quarter of these deals (23%) happened in Southeast Asia; 19% in Eastern Africa; and 16% in South America. There are also 810 concluded land deals involving domestic investors. More than a third of these deals (34%) happened in South America; 22% in Southeast Asia; and 11% in Eastern Africa.

These are the same regions where PANAP has monitored a high incidence of human rights violations related to land conflicts and struggles. In terms of killings, for instance, the highest number of victims were monitored in Southeast Asia’s the Philippines (33) while there were also victims in Cambodia (3), Indonesia (1), and Myanmar (1). South American countries also figured prominently – Guatemala and Mexico with nine victims each; Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela with five victims each; and Honduras and Peru with two victims each. Eastern African countries Kenya (2 victims) and Tanzania (1) also registered victims of killings.

The reported repression of rural peoples in the Philippines has been particularly alarming. This year, PANAP has monitored, as mentioned, 33 victims of killings that are related to land conflicts and struggles. Aside from extrajudicial killings, farmers, indigenous people, and advocates of the people’s rights to land and resources in the country are also subjected to arrests, detention and legal persecution (84 victims) as well as threats, harassment, and physical assault (36 victims). Some 3,688 Filipinos have also been displaced from their rural communities this year due to the government’s military campaign. All these are happening amid what many critics and observers (in the Philippines and elsewhere) say is an increasingly authoritarian streak of the populist incumbent, Pres. Duterte. There are now eight separate reported incidents of massacre of farmers and indigenous people under the less than three-year old regime. Martial law remains imposed (in place since May 2017 and most likely to be further extended) in the country’s southernmost region of Mindanao, where many of the killings and other atrocities against mostly indigenous communities (the lumad) are reportedly taking place.

A similar fate awaits rural communities in Brazil where another authoritarian populist with close ties to big agribusiness now reigns. Critics point out that Bolsonaro is being actively supported by the “Ruralista bancada” (the Parliamentary Front of Agriculture or PFA), the most influential agribusiness lobby group in Brazil. The new president has already appointed the head of the PFA as his agriculture chief. These developments are creating conditions for greater rural unrest and conflict in the country, where the landless campesinos and indigenous peoples, and landlords and big business are engaged in escalating struggles over land and resources. On top of the five victims of killings related to land conflicts and struggles that PANAP has monitored in Brazil this year, there were also at least one victim of arrest/detention/legal persecution and three victims of threats/harassment/physical assault in the country.

Even some of the political leaders in the region long notorious for their strongman rule are also making populist pitches to stay in power. For example, Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen who has been ruling the country for more than three decades as the world’s longest-serving head of government, has made pledges to supposedly return land ownership to the communities for farming purposes. Hun Sen again won this year’s elections amid accusations of systematic crackdown on the political opposition and critical media. Meanwhile, displacement and repression of rural communities continue contrary to Hun Sen’s earlier promise.

In a fact-finding mission that PANAP co-organized last September in nine villages in the province of Preah Vihear, reports were confirmed of lack of access to and control over some 13,000 hectares of land of the indigenous and farming communities due to the sugarcane operation of a Chinese state-owned company. (Download the summary of the mission’s report here) Last November, a march of more than 1,000 farmers and indigenous people from five provinces in the country (including Preah Vihear) were prevented from submitting to various government agencies in Phnom Penh their petition to settle their land disputes with local landlords and Chinese investors. PANAP has monitored three victims of killings in the country that are related to land conflicts and struggles this year as well as seven victims of arrest, detention and legal persecution.

Regardless of what is obviously a far more difficult situation today confronting farmers, indigenous people, and their supporters, hope remains that the people’s collective right to land and resources and to development will be realized and respected. The hope lies in the fact that amid the increasingly repressive environment that the rural communities are forced to bear, their determined assertion of their rights and aspirations remains strong as ever.

Land occupation and collective cultivation campaigns in the Philippines persist despite the massacres, threat, and intimidation. In Brazil, campesinos occupying and cultivating a disputed land in the Quilombo Campo Grande resisted an agrarian court’s eviction order and clinched victory after the order was reversed last November. Across India, tens of thousands of farmers are participating in a series of historic marches to demand, among others, that the government recognize their right to land and to stop infrastructure projects that cause their dislocation. In Cambodia, communities continue their resistance against land grabbing by foreign firms including through the filing of landmark court cases and class-action lawsuits.

These are just some of the stories of resistance and to be sure many others are happening as rural communities around the world carry on their struggle for – as what the Universal Declaration of Human Rights outlined 70 years ago – equality, justice, and human dignity. ###

Reference: Ms. Sarojeni Rengam, Executive Director (nolandnolife@panap.net)

Discussion about this post