Food And Rights Talk is a series of interviews with PAN Asia Pacific (PANAP) partners across the globe to find out the situation of rural peoples, in relation to food security and human rights, amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Food And Rights Talk is a series of interviews with PAN Asia Pacific (PANAP) partners across the globe to find out the situation of rural peoples, in relation to food security and human rights, amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

We interview Danilo “Ka Daning” Ramos, chairperson of the Peasant Movement of the Philippines (Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas or KMP). KMP is a movement of landless peasants, small farmers, farmworkers, rural youth and peasant women with 65 provincial chapters in the Philippines.

PAN Asia Pacific (PANAP): What are the most significant impacts that COVID-19 pandemic on the daily activity and livelihoods of farmers in the Philippines, based on reports from KMP members?

Ka Daning: The past almost 8 months, the impact of COVID-19 is greater poverty, hunger, and fear among farmers, agricultural workers and fisherfolk. Even before the pandemic, they’ve been impoverished because of feudal and semi-feudal exploitation, lack of support for farmers, import liberalization and other government policies. Now there is greater fear because instead of medical solutions, the government employs military action to control the pandemic.

Farmers fear for their health and safety. Under the so-called Enhanced Community Quarantine, farmers were unable to go out of their homes, their production was affected. In several KMP chapters, farmers were unable to sell their products, many of which were wasted. Although the government’s Inter-Agency Task Force said that agricultural production and transport of agricultural goods from provinces to the National Capital Region will be allowed, but a lot of reports indicate that they weren’t.

PANAP: So they weren’t allowed to go to the fields?

Ka Daning: In the beginning, a lot of farmers were afraid to because there’s this list of Authorized Persons Outside of Residence. A significant number of farmers are senior men and women who aren’t allowed to go out. That had an effect. But in the provinces, the reality is that houses are far away from each other, so farmers are free to go out. In my experience, I was able to leave Manila and go to my home province. I was able to plant on my fields—bitter gourd, ladyfingers, eggplant, sweet potato, and other vegetables. So during this period we are able to harvest when our household needs something to eat. We thought that the lockdown will only last a few months but it has lasted for longer.

PANAP: What about the impacts on fisherfolk?

Ka Daning: There is also a huge effect on the livelihoods of fisherfolk. For instance, in the province of Sorsogon, there were reports that the selling price of one vat of fish went down to Php 100 (USD 2). They couldn’t take it to the market because the ports were closed, and in general, the government doesn’t have a mechanism to buy local produce.

PANAP: How is the food security situation in the country both in the urban and rural areas?

Ka Daning: In the countryside, those who produce food have nothing to eat. Meanwhile, in urban centers, more people are experiencing hunger and begging on the streets. Research from the FAO shows that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of Filipinos who went hungry jumped by 31%. There were 44.9 million hungry Filipinos from 2014 to 2016, and it increased to 59 million from 2017 to 2019, according to a FAO study that was released on July 2020. The FAO’s State of Food Security and Nutrition also listed the Philippines as having the biggest number of food insecure citizens in Southeast Asia compared to Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam. One of the factors is that food production, which relies heavily on small farmers and fisherfolk, has little government support.

So even before the COVID-19 pandemic, rural people have already been suffering from hunger and food insecurity. Farmers and consumers alike have been impacted by rice trade liberalization in a negative way. Government spends spends billions of pesos in importing rice even if the Philippines is an agricultural country. We also import meat even though there is enough chicken and pork supply in the country, because of the thrust of the government to import under neoliberal policies imposed by the World Trade Organization and the program of imperialist globalisation.

PANAP: Have food prices increased?

Ka Daning: The Department of Agriculture (DA) rolled out the KADIWA Program to stabilise food prices, but data shows that it does not really result in lower prices. For instance, the price of commercial rice remains high. Even before the pandemic, the cheaper National Food Authority (NFA) rice was unavailable, so people are forced to buy rice at higher prices, at Php 42-45 per kilo, while premium rice is priced Php 50 (USD 1) per kilo or more. The government does not implement a price ceiling so the traders can impose whatever price they want. Rice traders monopolise the buying of rice in the countryside because under rice trade liberalization law, the NFA doesn’t buy local rice anymore. So big rice cartels—who in practice are also the big rice importers—monopolises the buying, milling, and selling of rice at the price they want.

PANAP: What are the measures that the government have done to ensure food security? Are these measures enough?

Ka Daning: At the height of the pandemic, the government launched a Plant, Plant, Plant program through the DA. Its main component is financial assistance to rice farmers, retail on wheels and online, urban agriculture, and food logistics. Unconditional cash transfer is worth Php 5,000 (USD 103) for eligible farmers who must be registered with the DA and own one hectare of land and below. The DA’s target is 591,246 rice farmers. But there are 2.7 million rice farmers in the country. So the target is already way below the total number of farmers. An altogether different issue is if this aid reaches the intended beneficiaries, and we’re getting a lot of reports that it does not. Coconut farmers, agricultural workers, and fisherfolk are also not included in financial assistance.

Secondly, the program focuses on food logistics—the DA allotted Php 20 billion for marketing alone. Who will profit from this? The merchants, traders, big corporations, landlord-usurers, and cartels engaged in trading and marketing. In contrast, they allocated such a small amount to production. But you first have to develop agricultural production so that you have something to sell. The money should be given instead to the 9.7 million Filipino farmers, fisherfolk, and agricultural workers so they have something to sell in the first place. Another point is on urban agriculture. We aren’t against it—those in urban areas should be encouraged to plant in their backyards. But if you look at the National Capital Region, more than one-third are informal settlers, urban poor who don’t have a house or have no space for gardening at all.

It’s not the role of the government to sell products to consumers in Manila. Their main role is to develop local production and food self-sufficiency in our country. But production assistance is almost non-existent, like a single drop of rain in a vast rice field. What’s worse is that even amid the pandemic, corrupt government officials are having a field day. During April to May, the government purchased Php 1.8 billion worth of fertilizers at Php 995 per bag. The commercial retail price of one bag of urea fertilizer is only Php 810-850, so the cost of government procurement per bag should’ve been cheaper since they bought in bulk. So at the minimum, we estimate that fertilizers were overpriced by more than Php 271 million (USD 5.58 million). So here you have farmers already suffering, and yet the little aid that is due to them is even being stolen by corrupt officials. That’s how bad the system is.

PANAP: The Philippines has among the highest COVID-19 cases in Southeast Asia. Why do you think this is so?

Ka Daning: The COVID-19 pandemic is a medical problem, and yet the government response is military action. Those who are in key positions leading the pandemic response are ex-generals. So when COVID-19 positive cases increased in Cebu province, they sent Special Action Forces instead of additional doctors and nurses. But even before the pandemic, the government didn’t prioritise fixing the health system. It’s not in its budgetary priorities. For instance, the Department of Health budget for 2020 was reduced. The Research Institute for Tropical Medicine in 2019 got more than Php 200 million, in 2020 it only got Php 115 million. And that the primary institution we rely on for testing. A lot of hospitals had their budgets cut. So health workers are paid little but overworked.

The government wants to blame Filipinos who don’t follow rules and protocols for the rising number of COVID-19 cases. But according to a survey, an overwhelming majority of Filipinos follow protocols such as hand washing, physical distancing, and wearing of face masks. In South Korea, before the government imposed face mask wearing as a policy, the government gave the people masks. Here, the government doesn’t give out face masks, and lately they even imposed face shields. We know the importance of these protocols, but we need the government support. If you have just a little money, before you buy alcohol, you will first buy food for your family.

PANAP: Do rural people have access to healthcare and COVID-19 testing?

Ka Daning: The rural poor don’t have access to healthcare. In rural areas, there are limited doctors, usually only municipal or city health officers who don’t go to the villages. Access to COVID-19 testing is even more limited. For instance, when I went home to my province from Manila, I asked the local government if I can get tested, and they said no. It’s safe to assume that there are a lot more COVID-19 cases that have not been tested and identified.

PANAP: Recently, one of your top peasant leaders, Randall Echanis, was killed inside his home by suspected state security forces. Would you say that attacks against farmers have increased during this pandemic?

Ka Daning: Yes, state-led attacks against rural peoples have been increasing and becoming more violent. Amid the pandemic, President Duterte signed the Anti-Terrorism Law, which allows the government greater—even unconstitutional—powers that can be used against critics and activists. Last May, six farmers and village officials were arrested in Calaca, Batangas province on trumped-up cases. Elena Tijamo, project officer of Farmers Development Center based in Cebu, was abducted at her home after dinner last June. Last April, the police arrested nine relief operation volunteers for farmers in Norzagaray, Bulacan province. As you already mentioned, our deputy secretary-general Randall Echanis was tortured and brutally killed on the early morning of August 10, along with his neighbour Louie Tagapia. Just two days ago, Zara Alvarez, a human rights worker and very active in the struggle of Negros farmworkers, was killed. We were together in many fact-finding missions, investigating the series of massacres of sugar workers whose main perpetrators were state security forces. We are calling for immediate justice for the killing of Zara Alvarez. There have also been massive bombings in farming and indigenous peoples communities across the country, especially in Mindanao, including Lumad schools where they practice and promote agroecological farming.

PANAP: Why is this happening?

Ka Daning: Under Executive Order 70 or the Whole of Nation Approach to ending local insurgency, it uses the entire state machinery, including the judiciary, against activists and ordinary citizens. In Negros, EV, Bicol, Memorandum Order No. 32, counter-insurgency program. What’s happening is that the Duterte government can no longer rule in the ordinary way, and so it resorts to the iron fist. I think that worldwide, its tyrannical and dictatorial rule is only second to that of Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro. But we believe that farmers, the toiling masses won’t be afraid and will continue to resist the terrorism of the state in many ways.

PANAP: How is KMP helping farmers cope with impacts of the pandemic?

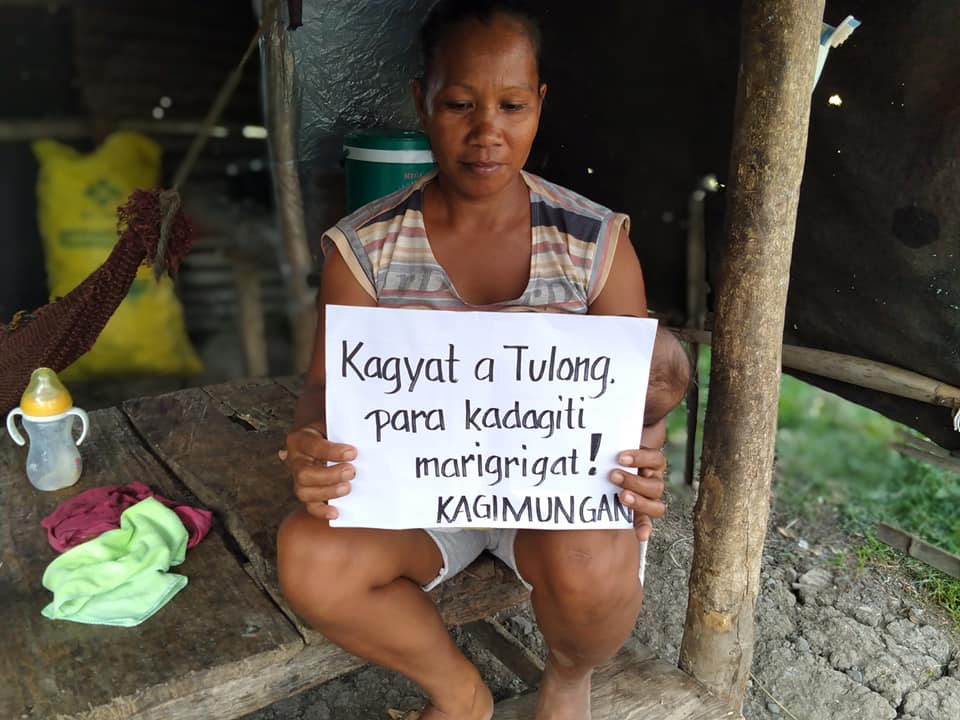

Ka Daning: Farmers practice bayanihan, or the tradition of helping each other out through this period of hardship and hunger. They show solidarity in facing the pandemic. Despite harassment, KMP has conducted relief operations (called Tulong Anakpawis) in the regions of Central Luzon, Central Visayas, Eastern Visayas, Bicol, and Ilocos to help farmers, agricultural workers and fisherfolk in need. We have this Bagsakan market where farmers’ produce are sold in urban centers. We also initiate livelihood programs so that their products are processed and don’t go to waste. In Bicol and the island of Mindoro, we worked with the local government so that instead of giving away canned goods as relief, they bought and distributed local agricultural products such as vegetables, fish and pork.

PANAP: Are there are any positive developments on the ground despite the hardships amid the pandemic?

Ka Daning: As I’ve already mentioned, farmers help farmers in different ways. Our advocacy campaigns continue. At the hearing of the House of Representatives on the COVID-19 stimulus package, KMP made concrete demands such as Php 15,000 immediate cash assistance, production subsidy, and production loans to 9.7 million farmers. We hold webinars, fora, and other activities. Farmers don’t give up and continue to struggle for their interests. This month, the planting season will once again start in many parts of the country. In our province, the land is ready for cultivation and some farmers are already starting to plant. In relation to this, we must struggle for genuine land reform and national industrialization. We need enough, safe, and affordable food through sustainable agriculture or agriculture that is free from chemical fertilizers and pesticides that are bad for our health. The issue of farmers is the issue of the people as a whole—not just in the Philippines but globally. So the continuing support of other sectors to genuine rural development is important.###

Discussion about this post