PENANG, Malaysia – Even before the spread of COVID-19, another “pandemic” has already been spreading terror in many rural communities worldwide. Killings, arrests, harassment and other forms of repression have been the daily reality of many poor peasants and indigenous people asserting their rights to land and resources. Data show that the trend worsened in 2020, aggravating a year already made extremely tough for the most vulnerable sectors by the COVID-19 pandemic.

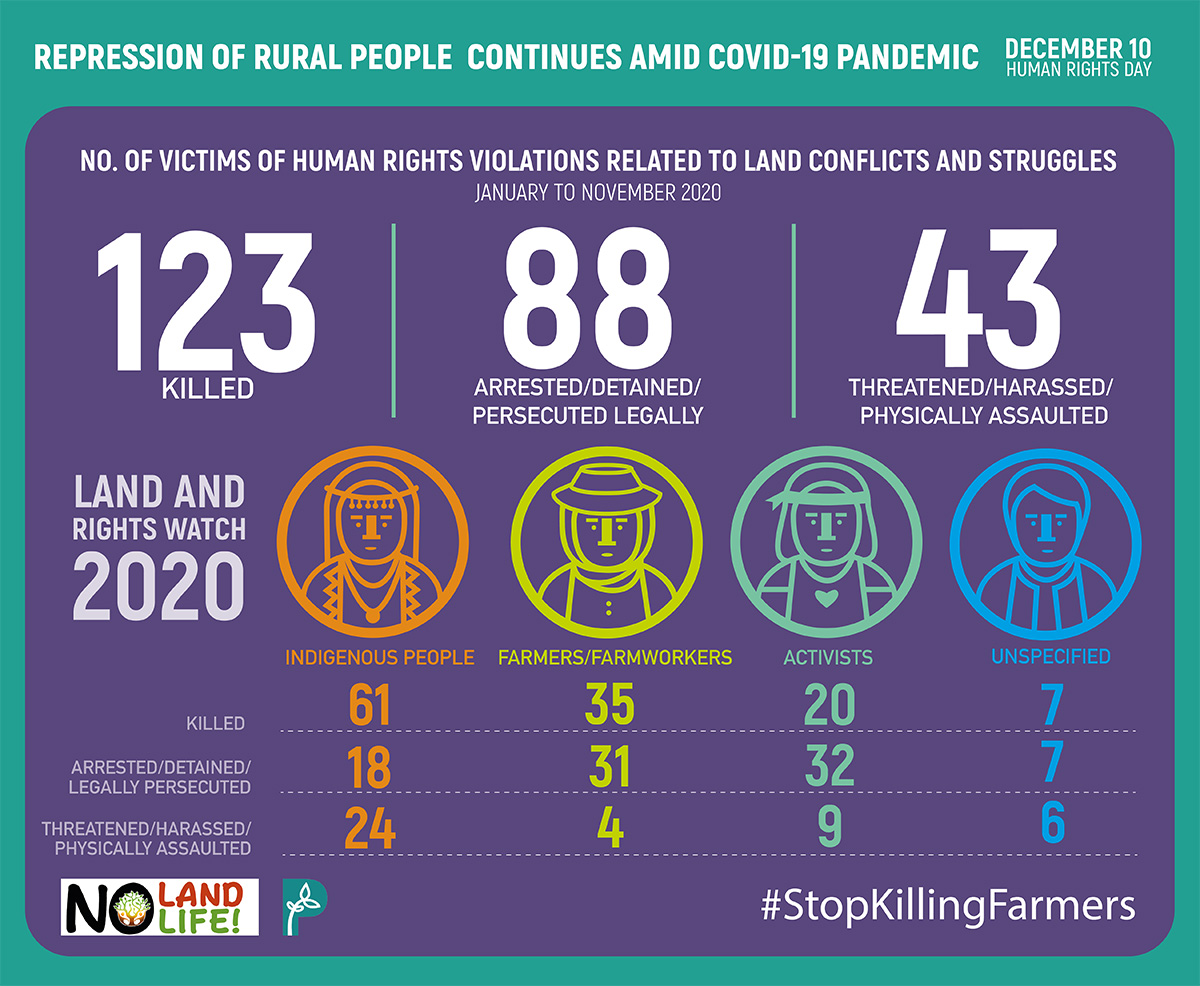

PAN Asia Pacific’s (PANAP) Land and Rights Watch monitoring revealed that 123 rural people were killed from January to November this year. During the same period in 2019, PANAP monitored 108 victims of killings related to land struggles of rural communities, or an increase of 15 victims from last year’s total.

Of those killed this year, 61 were indigenous people while 35 were farmers and farmworkers; 20 were advocates of the people’s right to land while seven were not identified in reports as belonging to a certain sector.

The advocacy group disclosed its findings as the world marks Human Rights Day on December 10.

“Rural people are among the biggest victims of human rights abuses. Impoverished and marginalised by governments in favour of big business agenda, they are extremely exposed to atrocities by those who desire their farms, ancestral lands and other resources for profit-making,” said PANAP executive director Sarojeni Rengam.

Almost half of the killings happened in Colombia where PANAP monitored 56 victims, 28 of whom were indigenous people. Civil society groups have noted the enormous increase in the incidents of killings of human rights defenders in Colombia, including leaders of indigenous communities.

One of them was Rodrigo Salazar, an indigenous leader of the Awá ethnic group. He was shot and killed by unknown assailants last July 7 in Llorente, a town in Colombia’s Pacific coast. Prior to his murder, Salazar was an advisor to a network of indigenous men and women who protect their ancestral domain from armed groups trying to control their lands.

Behind Colombia is the Philippines, where PANAP monitored 26 victims of land-related killings. The country has been notorious globally for the grim state of human rights under President Rodrigo Duterte amid rising incidents of alleged state-sponsored killings and other rights abuses.

Eighteen of the victims were farmers and farmworkers such as peasant leader Jennifer Tonag, who was gunned down last January 17 on her way home in Catarman, a town in one of the Philippines’ poorest provinces. She was an active member of Northern Samar Small Farmers Association (NSSFA) that assists farmers displaced by land grabbing.

Mexico ranked third with 20 victims, with 15 of the victims killed in just one incident of mass murder. The gruesome massacre of 15 members (including two women) of the Ikoots indigenous group took place in Huazantlan del Rio, a village in the municipality of San Mateo del Mar in the Oaxaca State last June 21. The victims were beaten to death and their bodies were burned in what is considered “one of the most brutal attacks to shake the (Mexican) countryside in recent years”. They belonged to a community that has been opposing the development of a wind farm near their village.

Aside from Colombia, the Philippines and Mexico, PANAP also monitored multiple victims of land-related killings in Nicaragua (6); Indonesia (5); and Brazil (3). At least one victim was monitored in Costa Rica, Guatemala, India, Nepal, Peru, South Africa and Vietnam.

PANAP monitored as well cases of threats, harassment and physical assault and recorded 43 victims from January to November 2020, a significant jump from the 25 victims that the group monitored during the same period in 2019. Of the 43 victims, 24 were indigenous people; four farmers and farmworkers; nine activists; and six from unspecified sectors.

In addition, the group monitored 88 victims of arrests, detention and legal persecution. This was much lower than the 153 victims recorded in 2019. Most of the victims of this form of repression were land activists with 32 victims, closely followed by farmers and farmworkers with 31 victims. Eighteen of the victims were indigenous people while seven were from unspecified sectors.

These human rights atrocities occurred in the context of rural communities fighting land and resource grabbing and asserting their rights, with the COVID-19 pandemic creating additional challenges for farmers and indigenous people facing threats of displacement.

“As governments imposed strict lockdowns to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus, farmers and indigenous peoples became more exposed to land and resource grabs. Worse, as we have found out in our monitoring, the repression that they suffer in their rightful defense of their farms and ancestral lands against the vested interest of corporations, landlords, politicians and other powerful forces has further intensified amid the pandemic,” said Rengam.

With restrictions on movement due to COVID-19, farmers are unable to tend to their fields while some indigenous people are kept from forests. This created a favourable situation for land grabbers like private businesses to encroach their lands. in Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar and Nepal, for instance, incidents of illegal logging were reported as police and security forces enforced lockdowns. In the province of Bulacan, north of Manila, Philippines, the stringent lockdown imposed by the Duterte government stopped local farmers from going to their farmlands that are being claimed by a real estate developer.

Along with the lockdowns, governments started implementing as well neoliberal reforms like relaxing or reversing state regulations that tend to protect rural communities from land grabbing such as environmental norms for mining and industrial operations. In India, for example, environmental assessment rules for industrial projects were loosened even as, according to critics, “the COVID-19 pandemic has (already) complicated public oversight and canceled potential field reviews”. Similarly, Indonesia’s controversial Omnibus Law will deregulate environmental and social protection measures to attract foreign investments at the expense of the environment and vulnerable rural sectors who will be exposed to greater harm, including potential displacement.

Rengam warned that the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic combined with political repression and massive displacement of communities due to land grabbing will intensify social conflicts and unrest as she appealed to authorities to end the reign of terror and impunity in the rural areas. ###

Reference: Ms. Sarojeni Rengam, Executive Director (nolandnolife@panap.net)

Land and Rights Watch is a PANAP initiative to closely monitor and expose human rights abuses against communities opposing land and resource grabbing. The group culls the data and information from online news and articles and reports from its partners and networks. With this limitation, PANAP does not claim that its monitoring represents the true global extent of human rights violations that are related to land and resource grabbing and similar conflicts in the rural areas.

Discussion about this post