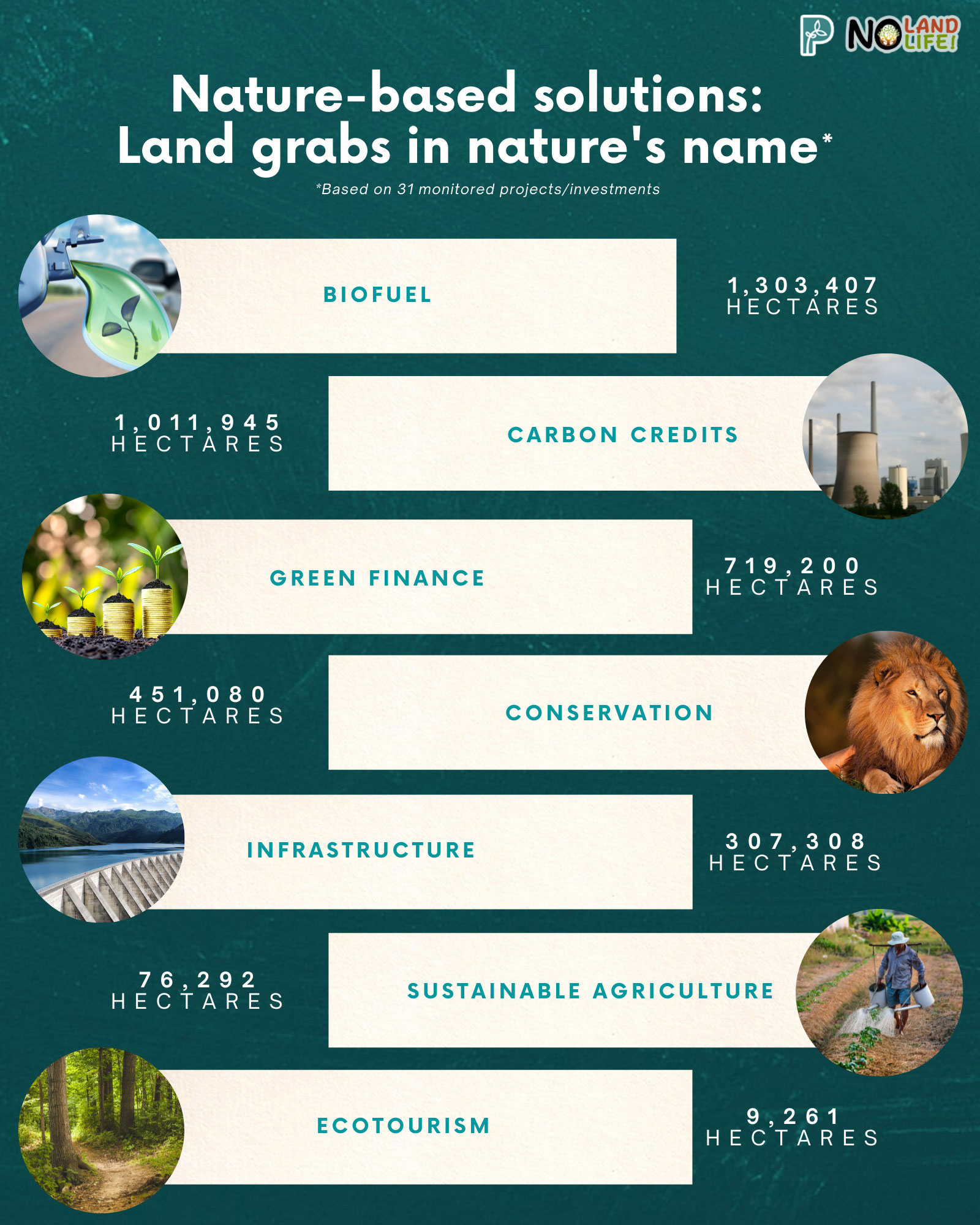

Expansion and consolidation of corporate control over land and resources loomed large in discussions organised by the United Nations (UN) last year on food (Food Systems Summit or UN FSS) and climate (Climate Change Conference of the Parties or COP 26). One of the buzzwords in these high-level meetings is “nature-based solutions” (NBS), also called nature-positive production. As part of their supposed climate action, corporations and governments have been pushing for NBS.

NBS, as defined by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), refers to “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems, that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits”. NBS looks good on paper, but many projects and investments by big corporate interests that are being peddled as NBS or nature-positive production result in or are feared to end in the massive displacement of rural communities.

PANAP compiled 32 such projects and investments (ongoing or planned) from various online reports. (See table for details). The operations of some of them and their impacts on rural peoples are summarised here.

“Sustainable” agriculture

Many corporations that style themselves as promoting “sustainable” agriculture to mitigate the impacts of industrial food production, in reality, deprive peasant communities of their homes and livelihood. PANAP monitored 76,292 hectares of lands covered by investments packaged as sustainable agriculture.

One of them is the 19,700-hectare sugarcane plantation of the Thai-based Mitr Phol corporation. The corporation is the third-largest supplier of sugar for Coca Cola and a perpetrator of human rights abuses in the province of Oddar Meanchey, Cambodia.

In 2015, the Mitr Phol corporation received the annual sustainability award of leading sugarcane initiative Bonsucro. Established in 2005, Bonsucro is a “global membership organisation that promotes sustainable sugarcane production, processing and trade around the world” to supposedly ensure that its member corporations in the sugar industry abide by sustainability and human rights guidelines.

Mitr Phol received the award even though the company displaced over 2,000 families and 26 villages in Cambodia to create its sugar plantations. Mitr Phol’s evictions include the burning and bulldozing of farmers’ homes and crops to make way for industrial operations.

Despite villagers’ repeated filing of grievance forms to Bonsucro, cases were dismissed on the grounds that Bonsucro had not received evidence of Mitr Phol’s breaching of its code of conduct.

The refusal of Bonsucro to acknowledge grave human rights violations in Oddar Meanchey prompted the UK National Contact Point to rule that Bonsucro breached the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

This shows how global multistakeholder platforms claiming to promote sustainable agriculture continue to protect corporate giants as they evict and harass smallholder producers from their homes and livelihood.

Biofuels

Biofuels have become popular as a nature-based solution due to their supposed ability to replace fossil fuels. Corporate proponents believe that the use of palm, corn, soy, and sugar monocrops to produce fuels doubles both as a renewable resource and a minor producer of greenhouse gas emissions. PANAP monitored over 1,303,407 hectares of lands utilised for biofuels with issues related to land grabs and displacement of communities.

Biofuels come with a litany of socioeconomic and environmental consequences. Research has shown that their production often necessitates mass deforestation, resource depletion, and with it, human rights abuses.

One such case occurred in the San Mariano province of the Philippines, where Green Future Innovations Inc. (GFII) invested USD 125 million to create a bioethanol plant spanning over 11,000 hectares to process the by-products of sugarcane crops for electricity as early as 2007.

The agricultural municipality of San Mariano at the time was populated by nearly 45,000 farmers and indigenous peoples owning or occupying the lands. Despite this, GFII claimed that the lands were idle and abandoned.

The rice and corn crops grown by farmers in the area were replaced with massive sugarcane plantations, effectively depriving them of their primary source of income while at the same time increasing soil degradation and food insecurity. The bioethanol plant was also responsible for massive fish kills due to the release of toxic wastes in surrounding farmlands and rivers.

In the years following the implementation of the GFII bioethanol project, the quality of farmers’ lives has rapidly declined. In 2015, an increase in respiratory illness in nearby villages was reported due to the mass ash particles produced by the plant. A year later, the plant’s operations were temporarily halted for failing emission and sewage disposal standards, which residents attributed as the cause of asthma attacks on children.

Farmworkers in the bioethanol plant have been threatened by paramilitary forces as recently as 2021. Soldiers in the area tagged the workers as insurgent rebels due to their participation in relief operations organised by the Philippines’ Union of Agricultural Workers (UMA).

Ecotourism

Ecotourism has been marketed as a sustainable alternative to traditional tourism due to its supposed higher regard for environmental conservation. Institutions have defined it as being able to conserve the environment and sustain the well-being of local communities. For this report, PANAP monitored 9,261 hectares devoted to ecotourism that adversely affected the local communities.

One example is the proposed 1,400-hectare Benoa Bay reclamation project of the PT Tirta Wahana Bali Internasional (PT TWBI) corporation in Bali, Indonesia.

Bali, a province in eastern Indonesia, has an extensive history of land grabbing due to its scenic beaches and cultural heritage. Large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) have become common in Bali since the 1980s to boost profitable tourist and infrastructure projects. It is estimated that in the last 25 years, Bali has lost over 25% of its agricultural land, and that over 85% of landowners in the area are non-Balinese.

Being one of the few remaining undeveloped and protected areas in Bali, Benoa Bay is composed of 1,300 of hectares of mangroves, rivers, and over 150,000 residents. Its protected status was revoked in 2014, which facilitated the corporate takeover of PT WBI for its megatourism project.

While PT TWBI has maintained that Benoa Bay’s reclamation is an eco-sustainable tourism project, over half of the area (700 hectares) was proposed to create artificial islands, restaurants, and entertainment venues, destroying mangroves and sacred Hindu temples in the process.

Research from the Faculty of Law of the Universitas Wijayakusuma Purwokerto of Indonesia has found that the reclamation project would destroy the area’s natural watersheds, trigger flooding conditions, and accelerate a widespread decrease in biodiversity.

Balinese Hindus have expressed condemnation for the project, highlighting the likely destruction of their ancestral customs and the increased vulnerability of flooding in their villages . Civil society groups, environmentalists, and the youth joined the growing anti-reclamation sentiment to form ForBali, a movement to protest PT TWBI. The movement was met with intimidation and police arrests to silence opposition to the project.

Conservation

Although conservation efforts are intended to preserve ecological systems, corporations have long colluded with national governments to cultivate protected land for profit. Among the largest land grabs for alleged conservation efforts includes the Ngorongoro Conservation area in Tanzania, which covers 150,000 of the total 451,080 hectares of lands found to be utilised for conservation sites.

Considered a UN Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site since 1979, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area is profit-driven and corporate-backed. In January 2022, the Tanzanian government threatened to evict over 70,000 indigenous Maasai individuals to create a wildlife corridor for trophy hunting and tourism. Behind the move is United Arab Emirates-based (UAE) Otterlo Business Corporation, an entity known for holding hunting excursions for the UAE’s royal families and guests.

Over 17.2% of Tanzania’s gross domestic product (GDP) is derived from tourism. Due to the country’s heavy reliance on the private sector, the national government continues to rely on foreign investments to strengthen its economy.

Long considered guardians of the environment, indigenous peoples are among the most vulnerable targets of human-rights abuses related to land conflict. In 2017, government-led evictions resulted in the burning of Maasai homes and the arrest of residents. Such instances of massive displacement are currently being implemented to make space for conservation areas, tourism, and hunting.

The possible displacement of the Maasai peoples has far-reaching, intergenerational effects. As threats to evict continue in 2022, Maasai are prevented from maintaining their cultural, environmental, and spiritual practices.

Renewable energy

Hydropower dams, wind turbines and solar powerplants are some of the common infrastructures that were built to generate renewable energy. With states and corporations looking for more lands to build them, renewable energy is becoming unsustainable and destructive to rural communities and their livelihoods.

About 4,500 to 5,000 people living near the Mekong River Basin were displaced following the construction of Lower Sesan 2 dam as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The USD 781 million dam is supposed to supply 80% of Cambodian capital Phnom Penh ‘s power supply, but villagers still use car batteries and firewood for their electricity needs. Worse, they could no longer catch the big fish they use to sell to support their livelihood.

In India, people are protesting against the K Rail project, a 529.45 kilometre semi high-speed rail corridor, for its impact on the environment. The Kerala state government highlights the environmental benefits of the rail. According to its website, it will run using 100% renewable energy and the whole operations will not use fossil fuels, thus reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. But the opposition claims that the rail corridor will pass through wetland, paddy fields and hills. Moreover, it is estimated that at least 20, 000 families will be displaced.

Based on the data compiled by PANAP, the infrastructure for renewable energy alone would need around 300,000 hectares of lands. The rising demand for renewable is driving more rural communities away from their lands, depriving them of their homes and livelihoods.

Green financing and greenwashing

Financial managers and corporations are putting their money on climate mitigation mechanisms to display their sustainability efforts as the climate crisis worsens. Under green financing, PANAP monitored 719,200 hectares invested in for monocrop plantations and carbon offsets.

Data shows that more agribusinesses are using so-called “green bonds” to show their sustainability efforts for the planet. Some companies or governments use green bonds to raise money for their operations that have supposedly environmental or climate benefits. However, known agribusinesses using green bonds are notorious for land grabbing and deforestation to expand their operations.

Soybean exporter Amaggi, for example, was able to raise USD 750 million in green bonds for 170,000 hectares of land while organic farm operator Rizomo Agro raised USD 5 million for its regenerative agriculture production covering 1,200 hectares, according to a report by GRAIN. Both green bonds are in Brazil, where deforestation continues for monoculture productions. Meanwhile, in Asia, AgriNurture Inc.–which exports agricultural produce from their plantations of mainly maize in Mindanao, Philippines–was able to raise USD 89 million of green bonds. In Indonesia, rubber plantation operator PT Royal Lestari Utama raised USD 95 million for a project covering 88,000 hectares.

Moreover, billionaires and pension funds are putting their money on farmlands that have the potential to generate carbon credits. In 2021, Microsoft founder Bill Gates was dubbed the largest private owner of farmlands in the US, owning 97,900 hectares of land. Meanwhile, Dutch pension fund PostNL launched its USD 220-million farmland fund called SDG Farmland Fund. In the US, the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAAA) has USD 8 billion investments for at least 1 million hectares of farmlands globally.

Putting their money on farms to generate carbon credits create an image to the public that corporations are socially responsible. However, the farmlands where money is poured into are tainted with land grabbing, community displacement and human rights violations.

The oil and gas sector, notorious as the most significant contributor to climate change, also aims to achieve its “net-zero targets” through carbon credits. According to Oxfam, these corporate giants are just “greenwashing” as they continue to extract fossil fuels for profit. It noted that Shell, BP, Total Energies and ENI would need to acquire approximately 48.5 million hectares of land to achieve their net-zero plans. Oxfam also projected that if the entire energy sector follows the same net-zero plans, 500 million hectares of land would be needed.

These nature-based solutions by corporations and the finance sector only mask their business-as-usual practices that contribute to the climate crisis, while at the same time worsening land grabbing, hunger and poverty, especially in the Global South. ###

#NoLandNoLife Features discuss recent developments, events, and trends on land and resource grabbing and related human rights issues in the region as well as the factors and forces that drive it. Send us your feedback at nolandnolife@panap.net.

Discussion about this post