The ‘pesticide treadmill’ refers to the situation wherein farmers find it difficult to stop using pesticides, since regular use often leads to pest or weed resistance, thus resulting in dependency on stronger or larger amounts of chemicals. It is an abysmal situation of millions of small-scale food producers. In this feature, Vietnamese farmers tell in their own words how it’s like to be caught in this toxic treadmill—and what they need to get out.

Nam Dinh, Vietnam—On 2nd September 2019, Mr. Lai Van Truong wife cut several stalks of morning glory (water spinach) growing near their rice field, which was sprayed with pesticides four days ago. The vegetable stalks were meant for their pigs, but since they looked young and fresh, she also cut a few tops for her family to eat. The next day, Mr. Truong went to work as usual. But shortly before noon, he started feeling very tired and uncomfortable, so he went back home to rest.

“I fell down as soon as I opened the door. I tried myself to drag myself inside the resting room since there were no one else in the house at that time. Then I tried to call the nurse at the commune infirmary to ask for prescription medication. However, because I was too tired and could not speak clearly, the nurse thought I had a simple fever, so he advised me to buy anti-fever medication. After taking two pills, I still did not feel better. Then, I started having diarrhea. The more water I drank, the more diarrhea I had,” he said.

Mr. Truong was advised to go to the district hospital, where he received treatment and medication for poisoning. He was confined for 12 days. “Now, when think back, if I went to the hospital too late, I might have lost my life,” he said.

While his wife and son also had diarrhea after eating the vegetables, Mr. Truong thinks he experienced more severe poisoning because he was involved in spraying two bottles of pesticides—BASF’s Fastac 5EC (alpha-cypermethrin) and HexAvil 5SC (hexaconazole)–on their rice fields a few days before.

Both alpha-cypermethrin and hexaconazole are considered by Pesticide Action Network (PAN) as Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs). They are banned in 29 and 35 countries, respectively.

Stories of poisoning

It is estimated that 385 million farmers and farmworkers around the globe suffer from acute unintentional pesticide poisoning each year.

Ms. Nguyen Thi Mau, 64, has been spraying pesticides for more than 20 years in her own fields and as a hired laborer. She has watched her own health deteriorate throughout this period. “One time when I was hired to spray pesticides, I accidentally poured pesticides onto my whole body because the aerosol cover was not tight enough. I promptly jumped into the river to wash off the pesticides, and then continued to spray. That time, I was very healthy and I was okay with the accident,” she said.

Now, her situation is different. While she does all sorts of things that she believes can help her detoxify—such as drinking lots of water, a ginger-sugar concoction, and rubbing salt and lemon on her hands and feet after spraying—she is aware that these do little to protect her. “My body is weaker. Just spraying around ten pesticide aerosols makes my limbs exhausted. I have been suffering from body pain for over a month now, getting dizzy and nauseous almost every afternoon, even when I do not spray pesticides.”

Like most other farmers in the agricultural district, Ms. Mau does not use Personal Protective Equipment such as gloves, boots, plastic coveralls, goggles and facemask because it they are too hot and uncomfortable to wear. Like most farmers, she would wear substitute PPE that would give minimal protection.

“I just wear my long-sleeved shirt and long trousers. I cannot wear a facemask because I cannot breathe. I do not wear boots when walking in the fields because it is easy to fall—I might spill the pesticides on myself. I feel comfortable wearing long socks instead.” She admits that not using protective equipment may have affected her health, but that she had to accept this—”otherwise I cannot work at all.”

The International Code of Conduct on Pesticides Management Article 3.6 states that “Pesticides whose handling and application require the use of personal protective equipment that is uncomfortable, expensive or not readily available should be avoided, especially in the case of small-scale users and farm workers in hot climates.”

Despite this, governments and industry continue to promote pesticides use even if PPE cannot realistically be used by farmers in many countries in the Global South. “It is too hot and uncomfortable to wear plastic coveralls in summer,” said Ms. Bui Thi Loan, 52.

Ms. Loan has been farming she was little. She could recall three instances when pesticides spilled on her body. Now, she is now experiencing chronic effects of poisoning. “I suffer from bronchitis or cough due to inhaling pesticides. I have coughing fits that last for about 2 weeks. This happens two to three times a year,” she said.

Reliance on pesticide sellers

Many farmers are not aware of the names of the active ingredients in the pesticides they use, much less if they are considered highly hazardous. Instead, they rely on sellers to recommend the pesticides and usually accept these recommendations without question, simply trusting their advice.

“Just go and talk to the seller to describe the diseases of the crops if you want to buy pesticides,” said Ms. Cao Thi Phuong, 61. While she mixes five to six kinds of pesticides for her rice and vegetable fields, she cannot recall the names of most of these “due to their foreign names.” Ms. Loan relates the same thing: “I do not pay attention too much to the name of pesticides. I just go to the store and ask the seller which kind of pesticides to buy, and they find and give me the products.”

Mr. Ngo Van Khoat can sometimes spray up to 40 aerosols per day. Despite his long experience as a hired sprayer, he still relies on sellers to tell him what kind of pesticides he needs and how much to spray. “The herbicide I use is burnt grass (spraying the herbicides on the surface makes it burnt), but I don’t remember its name…The same with insecticides. I just tell the pesticide seller the name of worm, such as silk worm, flying worm, etc. and they will give the pesticides,” he said.

While Khoat didn’t use to suffer any symptoms of poisoning in the past, this has changed for the past two years. Nowadays, he often gets dizzy, has blurred vision, elevated blood pressure, and occasional knee pain. “My hands turn purple, and sometimes they feel as if they’re shrinking. Sometimes when I’m driving the motorbike, I feel dizzy and my hands go numb, so I have to stop driving for a while.”

The doctors tell him that he has likely been poisoned by pesticides. “But I do not know which kind of pesticides I got poisoned with. Even the district hospital does not know because I have sprayed so many kinds of pesticides,” he said.

The supplemental income earned by farmers through spraying pesticides on other people’s farms can be quite significant—an incentive to keep doing hazardous work. For instance, Mr. Mai Van Phong earns up to VND 5 to 6 million as a hired sprayer. “I never ask the customer about which kind of pesticides they bought. If the customer does not tell, I will never ask.”

He does not store pesticides in their home out of fear that his grandchildren would eat them; he knows how toxic these chemicals can be. “I get poisoned one to two times each spraying trip, or no poisoning if I am lucky. In 2019, I got poisoned three times. It feels uncomfortable—my stomach aches, my body itches and I feel like I have a hangover,” he described.

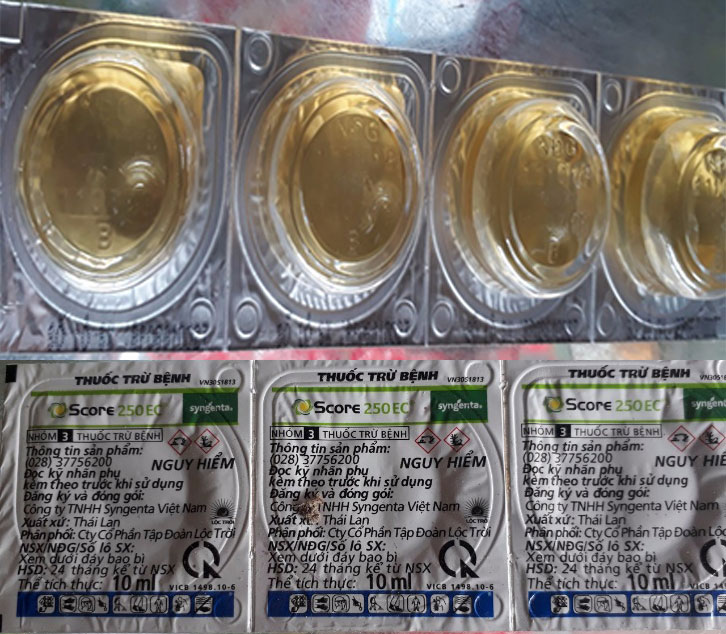

Ms. Nguyen Thi Hoang, 53, affirmed that local farmers do not know the English names and active ingredients of the pesticides they used. They mainly refer to pesticides based on the disease they “treat” or even, the shape of the pesticides. One such pesticide, Syngenta’s Score (difenoconazole) is called by Vietnamese farmers as “thạch” (jelly), because its packaging is similar to that of a jelly snack. “This is very dangerous because in the hamlet, I know people who store the pesticide at home. Their children saw it, supposed it were jelly, and intended to unwrap it to eat. Luckily, their grandmother saw and stopped them,” she said.

Future without toxics

Due to their own experiences, many farmers expressed the desire to stop spraying pesticides and explore safer non-chemical alternatives.

“This year, I have seen my health go down. I am much weaker. My sons still told me to stop farming, but how can I stop? I still have to work, work until I can’t,” said Ms. Phuong.

Mr. Phong, who recently underwent an eye operation, thinks that pesticides use has affected his eyes. His children also do not like him to continue working as a sprayer. “I know that my pesticide spraying job is very hazardous, but I have to try my best to work. In the future, I will still spray pesticides if being hired, but with less frequency as I am old now. I have to take care of myself,” he said.

Many farmers, like Ms. Nguyen Thi The, 72, has heard of alternatives. “I have heard on television about compost, microbiological pesticides. However, people say that by using micro-biological pesticides, the leaves and fruits will not turn out beautiful, the customers will not like and buy the produce. But I also have to learn from experience. I know pesticides are poisonous to our health and in time, I have to use the microbiological pesticides to protect my health.”

However, farmers find it difficult to imagine how to stop using pesticides if they are to do it alone. “If I do not spray, but my neighbours spray, worms will all move to my gardens and fields. Therefore, it is impossible to do organic farming alone,” said Mr. Khoat.

Ms. Phuong echoes this sentiment, but is more optimistic that collective action can help farmers transition away from the use of toxic pesticides. “I have heard of organic agriculture, sometimes from workshops. But it is difficult to practice due to fragmented garden and fields. To practice organic agriculture, we must plan a cluster of fields to work together, sharing the methods, techniques, investment costs and irrigation equipment. Doing organic agriculture is good for the health, low cost, and has no harmful effects to farmers like me. My desire for the future is to practice organic agriculture. We, the women, desire that,” she said.

Written by Ilang-Ilang Quijano. Interviews by Nguyen Kim Thuy and Than Nguyen Phuong Hai of CGFED (Research Centre for Gender, Family and Environment in Development).

Discussion about this post