Ms. Le Thi Khuyen, a 62-year-old resident of Hamlet 4, Hai Cuong commune, Hai Hau district, Nam Dinh province, manages a 0.36-hectare rice field with her family. They grow two rice crops annually and tend to livestock. However, despite this backbreaking labour, Khuyen’s family struggles to make ends meet. They earn just over USD 40 to USD 81 per crop after deducting expenses.

To compensate, they also earn money through other means, including raising pigs and chickens and operating rice milling machines to serve the local community. When Khuyen was younger and healthier, she used to sell rice and paddy in local markets. However, she was forced to stop as she grew old and frail.

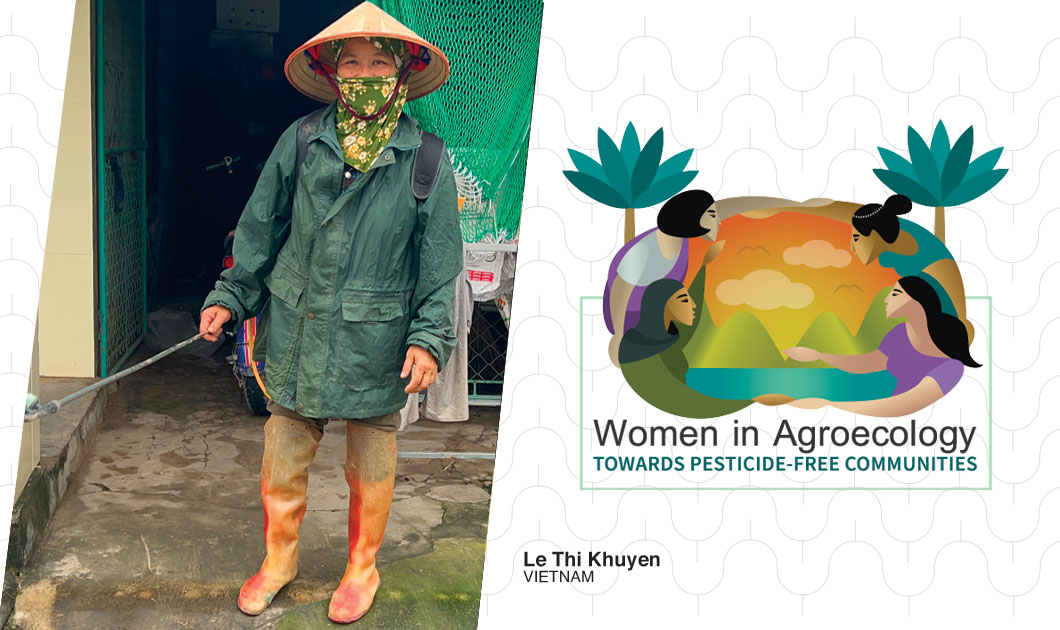

Her husband, who once handled pesticide spraying, suffered from pesticide poisoning and now battles health issues, including tuberculosis and gout. Since his illness prevents him from continuing this task, Khuyen has taken over pesticide spraying herself for the past three years, foregoing hiring help due to cost concerns.

Khuyen meticulously applies pesticides to her rice field, covering multiple types of pests and diseases, though she struggles with fatigue and discomfort afterwards. She typically sprays pesticides four to five times per crop, depending on the severity of pest infestations. Each spraying session usually addresses two to three types of pests and diseases, focusing on controlling hoppers and addressing issues like rice blast disease and Rhizoctonia Solani. Covering their rice field takes her an entire day, using approximately 10-12 pesticide spraying tanks. While a younger and healthier individual might complete the task in half a day with the same number of tanks, Khuyen’s age and health condition require a full day’s effort to complete the spraying.

Despite her many precautions, she experiences symptoms of pesticide exposure, including dizziness and nausea. She recognizes the environmental impact of pesticides, observing fish deaths in nearby water sources after spraying.

Because of these dangers, Khuyen recently opted for biological pesticides. However, she acknowledges their limitations in treating issues like rice blasts and planthoppers. She struggles with the probability that abstaining from pesticides could lead to crop loss and food insecurity.

Khuyen’s story underscores the harsh choices faced by farmers reliant on pesticides for survival. It further highlights the urgent need for safer agricultural practices. Through her experiences, she sheds light on the hidden costs of pesticide use and the importance of exploring alternative solutions for human health and environmental preservation.###

Women In Agroecology: Towards Pesticide-Free Communities is a continuing storytelling initiative of PAN Asia Pacific and its partners to document stories of rural women who are survivors of pesticide poisoning and/or making the transition to agroecology.

Our contributing partners for the second installation: Shikkha Shastha Unnayan Karzakram (SHISUK), Bangladesh; Serikat Perempuan Indonesia (SERUNI); Sustainable Agriculture and Environment Development Association (SAEDA), Laos; and Research Centre for Gender, Family and Environment in Development (CGFED), Vietnam

Discussion about this post